An Interview with Drew Boggio, Spacecraft Engineer at Impulse Space, former Mechanical Engineer at Joby and Virgin Orbit.

“I was not the greatest student. If I saw my college resume, I would not have hired me. What changed was learning how to think deeply, then practicing that on real hardware and with real people.”

What is your background?

I did not grow up dreaming about space but instead I loved anything that moved, cars, planes, or rockets. At Penn State I was more social than engineering club focused and my resume did not shine. The turning point came junior year in a tough physics sequence. I took a quantum class, read the textbook slowly, wrote meticulous notes, and fought to understand every line. That struggle rewired how I learn to this day. The grades followed, but more importantly so did the habits.

A mentorship program at Penn State paired me with Tim Buzza, an early SpaceX leader. He did not hand me a job, but instead widened my view of what is possible and pointed me toward teams working on those hard problems. When it came time to decide where to begin my career I dove head first into aerospace. At 20 years-old I drove from New Jersey to Los Angeles for an internship at an aerospace start-up. I could have chosen a less risky role with a government contractor, but I was drawn to the unknown and excited for a challenge. What started out as an internship at Virgin Orbit, turned into a full time role as a Responsible Engineer across design, analysis, test, and integration. I treated each domain like that quantum book, master the fundamentals, then build. The shop floor taught me people, how teammates are motivated, what they worry about, and how to help them win.

Critical thinking and truly struggling through all new problems was the key to my personal success at Virgin Orbit and later on in my career. One side of the brain automates quickly and the other reasons meticulously and slowly. The more I forced myself to think critically, whether it be a technical or people problem, the more I could transition similar future scenarios to the automation side of my brain. Through this approach I started slow, but as time went on my efficiency grew exponentially thanks to the previous “thought investment”.

After about a year I began to ask business questions like mass to orbit, frequency, and unit economics. My conviction in the long term trajectory softened. I looked for a steeper curve. Joby Aviation became that curve. The product was close to impossible; fully electric, vertical takeoff and landing, composite structure, novel mechanisms, FAA type certification, and human rated.

The team at Joby pushed my definition of a perfect part and of disciplined optimization because nothing short of perfect would meet the requirements for such a demanding vehicle.

Three years into my time at joby, I heard that Tom Mueller was starting Impulse Space. I was not actively looking for a new position at the time, but I knew that Impulse could offer me what Joby couldn’t: A small team I could help build, spacecraft with quicker design cycles from concept to flight, and a return to the Los Angeles aerospace network. The business case was not obvious on day one, but the people were truly world class. I bet on the team. At Impulse I owned critical subsystems including composite overwrapped pressure vessels, learned to deliver high quality at speed, and then moved into program architecture and people leadership. We proved Mira on orbit and helped shape Helios for real customers leading to a notable vehicle demand for both Impulse products.

Top three business lessons for engineers:

What have been your top career accomplishments so far?

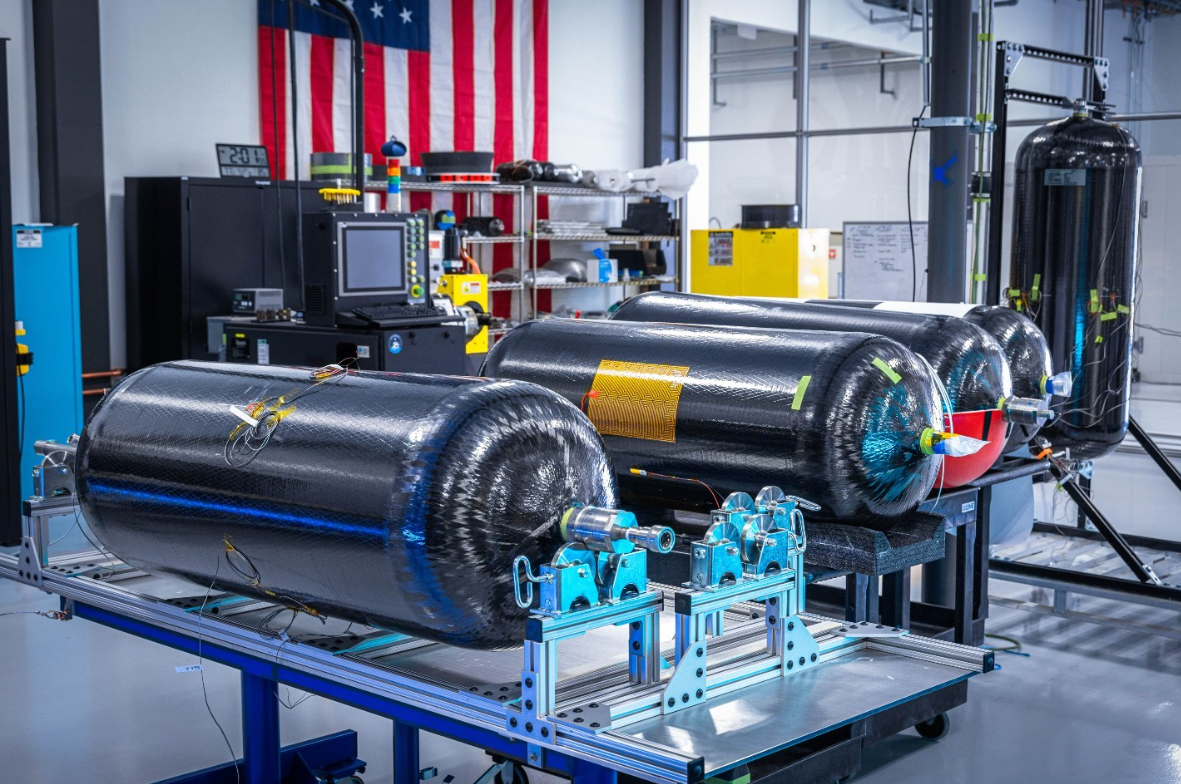

Composite Overwrapped Pressure Vessels on First Mira

COPVs are treated like a dark art because the risk is real. I convinced leadership to bring them inside, secured resources, planned the work at a granular level, and delivered on a tight schedule without lowering the quality bar. Seeing those tanks fly on a vehicle that exceeded expectations is a great memory of mine.

Mira Productization and Buy In

I helped move Mira from a single successful flight to a product with a clear market. As a team, we drafted multiple versions from the ground up, walked the concepts through product and business development, gathered feedback from real customers, and kept momentum with proof from tests and integrated demos. As interest grew we socialized a bottom up narrative that showed how Mira could win fast while the company also pursued the larger Helios vision. That work earned leadership trust and resourcing for multiple later vehicles that the market was asking for.

What were the critical steps or choices that helped you get ahead?

Train how you think. Repetition matters for fundamentals and empathy. Lean into your spike. I am effective at owning products end to end, architecting, sequencing, and driving to integrated tests, so I doubled down and expanded scope in deliberate steps. Choose environments that give both fire and scaffolding. Early at Virgin I had exposure to hard problems in a fast paced environment with seasoned rigor around me. Think beyond your box. Even as an individual contributor I mapped how our subsystem rolled into the business, which led to better choices and more scope.

What part of your education had the most impact on your career?

My internship. Classes gave me a base, but the internship showed me what is possible in industry and pushed my learning by doing mindset to the limit. I learned to move fast while honoring fundamentals and was guided by individuals who had solved ten versions of my problem previously.

What about your career have you enjoyed the most and least?

Most

Orchestrating a team so the work is both fun and excellent. The memory of a project is significantly more pleasant when you enjoy your time working on it. A manager sets calibrated exposure. Find what people are good at, place them where they shine, then widen their aperture at the right rate. Balance challenge and stress. When you get that balance right, people grow, culture stays positive, and you ship a spacecraft.

Least

Not being able to help. Watching people burn out or fail and not having the direct scope or ability to lead them towards success. Layoffs are painful, but slow and preventable failure can be worse. I focus on building the skill of influencing both up and across so teams are protected before they reach that point.

Where do you see the most promising career opportunities in the future?

Defense will accelerate key technologies and fund the hard things. The big unlock is precise control and maneuverability in space, including operations that move across orbits with speed and accuracy. We have long had mastery on land, sea, and air. We are now gaining it in orbit and beyond. That capability shift is why rapid orbit transfer, precise rendezvous, and proximity operations matter. They are part of the infrastructure for the in-space economy.

What advice or resources would you share with the next generation?

Find your edge and lean in. Do not chase prestige. Chase the thing you can become world class at and which you enjoy. Treat mastery like a staircase. Take the next step you can nail, then the next harder one. Pick mentors who expand your map. A single conversation can redirect your trajectory more than a year of classes. Early in your career, target teams that pair veteran rigor with startup speed so you get both proper learning and responsibility.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

You do not need a forever plan. It is fine if your path looks like aircraft to spacecraft or commercial to defense. Keep moving toward harder problems with better people, and keep practicing how you think.

Lessons for engineering managers