An Interview with Bill Murray, Co-Founder and Chief Engineering Officer at Ursa Major Technologies, former Propulsion Engineer at Blue Origin and SpaceX, Lab Leader at USC Rocket Propulsion Lab

What is your background?

I grew up in Kansas City, far away from the rockets being launched in Florida and California, but a plastic Space Shuttle my parents gave me when I was two was somehow imprinted for life. In high school I was the kid who tore through physics homework so I could get back to band practice; aerospace still felt like something “real engineers” did somewhere far away. I considered going to the Air Force Academy until I was awarded a scholarship to USC.

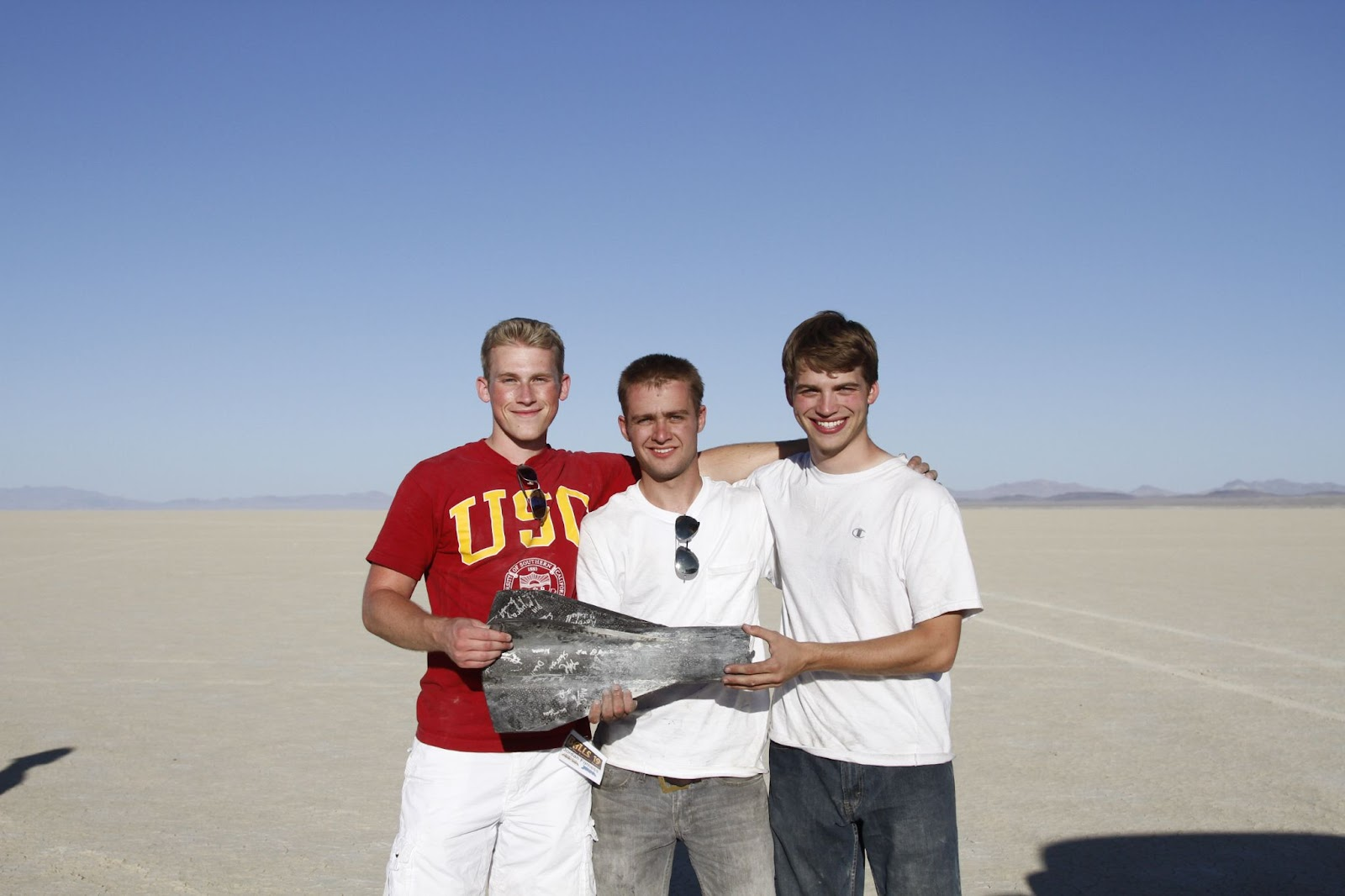

Landing at USC changed everything. During welcome week I wandered into an airplane-design club that already had fifty members and felt… crowded. I had heard about a group on campus full of aerospace students that liked to light things on fire in the desert. Two undergrads, David Reese and Ian Whittinghill, had convinced the dean into a few thousand dollars and a forgotten test cell in the Mojave. No competition trophies—just a moon-shot declaration. That audacity hooked me.

For the next four years I lived in that lab. I scheduled classes around static-fire days, pulled 80-hour weeks, and racked up four internships—two at Whittinghill Aerospace and two at SpaceX—while running RPL my junior and senior years. We weren’t playing with Estes kits; we designed an 8-inch-diameter carbon-fiber sounding rocket and after two painful years of paperwork I spearheaded the first student team to get an FAA waiver to punch space. The process taught me regulatory navigation, donor pitching, media briefings, and the adrenaline of lighting hardware you built with your own hands.

SpaceX super-charged the lesson. At twenty I was redesigning the Dragon nose cone and sitting outside of Mission Control when it docked with Station. The culture said, “If it’s the right idea and you can defend it, you own it.” That stripped away any hesitance about taking big swings.

I still wanted a deeper theoretical toolkit, so I spent two years at Purdue studying aero-mechanical blade dynamics for Rolls-Royce compressors—publishing papers by day and CADing peroxide rocket engines for fun at night. Fantastic education, but the quarter-percent efficiency tweaks convinced me I needed faster cycles.

Blue Origin—300 people at the time—gave me breadth. I rotated through aero-heating, turbomachinery, launch-site design, and gimbal design for BE-4. My row-mates became a who’s-who of future startups: Tim Ellis (Relativity), Glenn Case (Generation Orbit/Hermes), Tom Feldman and Andy Lapsa (Stoke).

When Joe Laurienti, another USC alum, called to say he’d raised “a couple hundred grand” to build an oxygen-rich engine in Colorado, I didn’t over-think it. Six of us moved into a loft above a medical-device company, rented an abandoned test site, and Ursa Major was born.

Fast-forward ten years: I’ve gone from modeling Hadley’s pre-burner to running Manufacturing, Engineering, Product, and now our entire Solid Rocket Motor division. I’ve lived through Series A euphoria, Series C scale-up, a Series D gut-check, layoffs, pivot into hypersonics, and our recent solid-motor win that re-energized the company. I stay because we keep learning faster than we stumble—and because firing an engine you helped dream up still sends chills down my spine.

What have been your top career accomplishments so far?

It has to be Hadley. Seeing America’s first oxygen-rich staged-combustion engine fly autonomously on a Stratolaunch mission was surreal. I still recognize parts I machined or designed late into the night.

On the business side, the recent solid-motor product we’ve built is truly innovative. In 2023 we were fresh off a market contraction, cash-constrained, and questioning identity. Joe asked me to spin up an internal “startup” around solids. We built a small skunk-works-style team, pulled in specialists from Tesla, propellant chemists and composites engineers from Indian Head & China Lake, and veteran chief engineering talent from Aerojet and Northrop. Twenty-four months later we had hot-fire data, a Mark 104 contract, a brand-new energetic-materials plant, and—crucially—a growing P&L that proved we could fuel our own growth. That program didn’t just save jobs; it repositioned Ursa as a multi-market propulsion house.

What were the critical steps/choices that helped you get ahead?

The most important one has been stepping in and supporting the biggest gap, regardless of my job title. At different moments I’ve been the guy modeling injector swirl, choosing an ERP, and briefing senators. Every time I leaned into an uncomfortable gap, I earned disproportionate trust and visibility.

Second, saying yes before I felt ready. Moving to Colorado on seed money, taking over Manufacturing with zero factory-management credibility, jumping into solids with only undergrad propellant work—each felt reckless. But competence compounds faster than confidence; I’ve learned to bet on the growth curve.

Third, treating education as R&D time. At USC I cherry-picked heat-transfer and composites electives because our student rocket needed them now. That bias toward immediate application carried into my career and keeps me experiment-minded.

What part of your education had the most impact on your career?

The USC Rocket Propulsion Lab, hands down. Classes taught me fundamentals; RPL forced me to weld, budget, certify flight hardware, negotiate range time, and manage forty volunteers who worked for pizza. Those are the exact muscles I use today—only the budgets and blast radii are bigger.

My master’s mattered, but mostly because it taught me how to teach myself. Publishing six journal papers in two years drilled a research cadence: define the unknown, prototype, test, publish, iterate. That meta-skill lets me jump from pump cavitation to ERP schemas to DoD acquisition pathways without panicking.

What about your career have you enjoyed the most and least?

Most: Building both the technology and the company. I’ve spent a decade learning how we design, build, and ship propulsion—and how we build the machine that builds it. I’ve sat in design reviews, run analysis, stood on the test stand, fixed factory flow, managed programs, worked with customers, pitched BD, set product roadmaps, owned a P&L, and hired the people who make it work. It’s the full stack of aerospace and operations, end to end. You don’t get that breadth of experience in many places.

Least: Layoffs. In 2023 I spent a Monday telling brilliant, loyal teammates that market reality trumped our runway. Necessary, yes, but gutting. The silver lining is that it forced ruthless prioritization and birthed the business-unit model we use today.

Where do you see the most promising career opportunities in the future?

I’m bullish on an in-space economy that pays its own bills—be it through power beaming, off-planet manufacturing, or resource extraction. Propulsion is the logistics backbone of that future; our job is to make moving mass around the Solar System boringly reliable.

What advice/resources would you share with the next generation?

Is there anything else you would like to share?

Don’t apologize for ambition. Hard problems demand hard work, and if you love the mission, the hours convert to memories, not regret.